Specials: Particle effects make it pretty.

If you've been following this series, you'll know that in the

first installment of Essential Tech, we talked about how most of the landscape and other objects in games are modeled in three dimensions and are represented using a mesh of vertices covered by some sort of texture that gives the mesh the illusion of solidity. And then in the

second Essential Tech article, we looked at how techniques like normal mapping can be used to add visual detail to a scene without adding more polygons. This time out, we're going to explore particle effects, another essential element of game art that doesn't use the standard vertex/polygon/texture setup that we might expect.

Vertices and polygons make sense for things with clearly defined shapes like buildings, cars and swords and so on. They have a structure that remains relatively constant throughout the life of the model. A car's tires may rotate or its bumper may deform in a crash, but the overall shape of the car is constantЧthose deformations are probably even pre-planned by artists and animators well in advance. On the other hand, phenomena like fire, smoke and other УfuzzyФ objects don't lend themselves to the precise structures that polys are so good with. Take a look at the screenshot from Call of Duty 2. The smoke billowing across the road is very different from the blocky buildings around it. The smoke is transparent in places and thicker in others. There's a randomness to its form and its edges suggest softness as it has spread out in the shot on the right, especially around the lower window. That's where particle systems come in.

Particle systems have been around for a long time. According to an article in the July 1998 issue of

Game Developer magazine, William Reeve laid the foundation for the modern particle effect system in creating Genesis Effect for the 1982 movie

Star Trek II: The Wrath of Kahn (Jeff Lander УThe Ocean Spray in Your FaceФ). The Genesis planet also involved a fractal system, but that's the subject for another article. Reeve's innovation lies in his giving structure to particle systems: he realized that a set of rules, things like speed, location, and lifespan, would allow him to create chaotic effects while keeping some control over the system. He ended up using as many as 400 different particle systems in the movie with some 750,000 particles. Not bad for 1982 hardware.

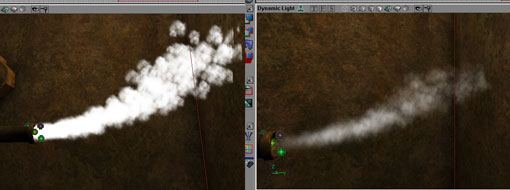

Modern particle systems are still based on these early roots. The visual element of the system is generally a

sprite, a single plane with an image applied to it. The best way to think of a sprite is as a billboard aligned so that its image always faces the player, no matter what the actual angle of view. Sprites can be made up of a single image or a series of animated images for more complicated effects. Animated sprites can be used in things like fire effects so that an individual flame changes shape as it flips through the frames of the animation. On the other hand, static sprites have been used for all kinds of effects like smoke, spraying water, and so on. In the simple particle emitter example from Unreal Editor, multiple copies of the same static sprite are clearly visible in this attempt at a basic steam effect.